Psychological testing, specifically intelligence tests, has long been a cornerstone of understanding human cognition. By critically evaluating its evolution, methodologies, and practical implications, this article aims to provide an in-depth, learner-friendly analysis.

1. Historical Development of Intelligence Testing

The concept of measuring intelligence dates back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, emerging from the efforts of psychologists to quantify cognitive ability scientifically. Key milestones include:

Early Foundations

- Francis Galton (1869): Galton pioneered the first attempts to measure intelligence, emphasizing sensory abilities. Though his methods were rudimentary, his work laid the groundwork for later developments.

- James McKeen Cattell (1890): Expanded on Galton’s ideas, introducing mental tests that evaluated reaction time and sensory acuity.

The Advent of Modern Intelligence Tests

- Alfred Binet and Théodore Simon (1905): Developed the Binet-Simon Scale in France to identify children needing special educational assistance. This was the first test to measure mental age.

- Lewis Terman (1916): Adapted and standardized Binet’s work into the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale in the U.S., introducing the concept of the Intelligence Quotient (IQ).

Wechsler Scales

- David Wechsler (1939): Created the Wechsler-Bellevue Intelligence Scale, later refined into the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) and Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC). Unlike earlier tests, Wechsler’s scales included both verbal and performance components.

Modern Developments

- John Raven (1938): Introduced the Raven’s Progressive Matrices, focusing on non-verbal reasoning.

- Howard Gardner (1983): Proposed the theory of Multiple Intelligences, challenging traditional IQ measures by introducing domains like linguistic, logical-mathematical, and interpersonal intelligence.

Timeline of Key Intelligence Tests

| Year | Test | Author(s) |

| 1905 | Binet-Simon Scale | Alfred Binet, Théodore Simon |

| 1916 | Stanford-Binet Scale | Lewis Terman |

| 1939 | Wechsler-Bellevue Scale | David Wechsler |

| 1938 | Raven’s Progressive Matrices | John Raven |

| 1983 | Theory of Multiple Intelligences | Howard Gardner |

2. Types of Intelligence Tests and Their Applications

2.1. Verbal Intelligence Tests

- Examples: Stanford-Binet, WAIS.

- Components: Vocabulary, comprehension, and verbal reasoning.

- Applications: Used in academic settings, job selection, and cognitive assessments.

- Case Study: A corporate organization used WAIS-IV to identify high-potential employees for leadership roles. Candidates scoring in the top quartile demonstrated higher problem-solving and adaptability skills.

2.2. Non-Verbal Intelligence Tests

- Examples: Raven’s Progressive Matrices.

- Components: Pattern recognition and abstract reasoning.

- Applications: Ideal for assessing individuals with language barriers or speech impairments.

2.3. Multiple Intelligence Assessments

- Examples: Gardner’s MI Test.

- Components: Measures domains such as musical, kinesthetic, and interpersonal intelligence.

- Applications: Widely used in educational settings to customize learning approaches.

| Test Type | Best Use Case | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Verbal | Academic assessments, clinical diagnosis | Language-dependent |

| Non-Verbal | Cross-cultural testing, language-impaired groups | Limited to abstract reasoning |

| Multiple Intelligence | Tailored learning programs, career counseling | Lack of empirical standardization |

Take a Free IQ Test

3. Critical Evaluation of Intelligence Testing

3.1. Strengths

- Predictive Validity: Intelligence tests, especially IQ tests, are strong predictors of academic and professional success (Deary et al., 2007).

- Standardization: Tests like WAIS and Stanford-Binet provide standardized scoring, ensuring comparability across populations.

- Clinical Utility: Identifying cognitive impairments like dementia, ADHD, or intellectual disabilities.

3.2. Weaknesses

- Cultural Bias: Tests often favor Western, educated, industrialized populations (WEIRD). For example, verbal IQ tests may disadvantage non-native speakers.

- Overemphasis on IQ: Focusing solely on IQ ignores other forms of intelligence, such as emotional intelligence (EQ).

- Misuse: Misinterpretation of results can lead to labeling or discrimination, as seen in early eugenics movements.

4. Practical Advice for Learners and Professionals

4.1. Interpreting Scores

- IQ Ranges: An IQ score of 100 represents the average, with 15 points as the standard deviation. Scores above 130 indicate giftedness, while scores below 70 may indicate intellectual disability.

- Tip: Always consider the confidence interval when interpreting scores. For instance, an IQ of 110 with a margin of error of ±5 points may range from 105 to 115.

4.2. Ethical Administration

- Ensure informed consent, especially in clinical and educational settings.

- Use culturally appropriate tests. For example, the Raven’s Matrices are better suited for multicultural populations.

4.3. Incorporating Results into Practice

- Educational Interventions: Use multiple intelligence profiles to design tailored teaching strategies. For example, a child strong in kinesthetic intelligence may benefit from hands-on learning.

- Workplace Applications: Incorporate cognitive testing into recruitment but supplement it with assessments of emotional intelligence and creativity.

| Actionable Steps for Educators |

|---|

| Identify student strengths using MI tests. |

| Combine test results with qualitative observations. |

| Design lesson plans catering to diverse intelligences. |

5. Recent Research and Advances

- Emotional Intelligence (EI): Studies suggest that EI predicts job performance more effectively than IQ in emotionally demanding roles (Goleman, 1995; Mayer et al., 2004).

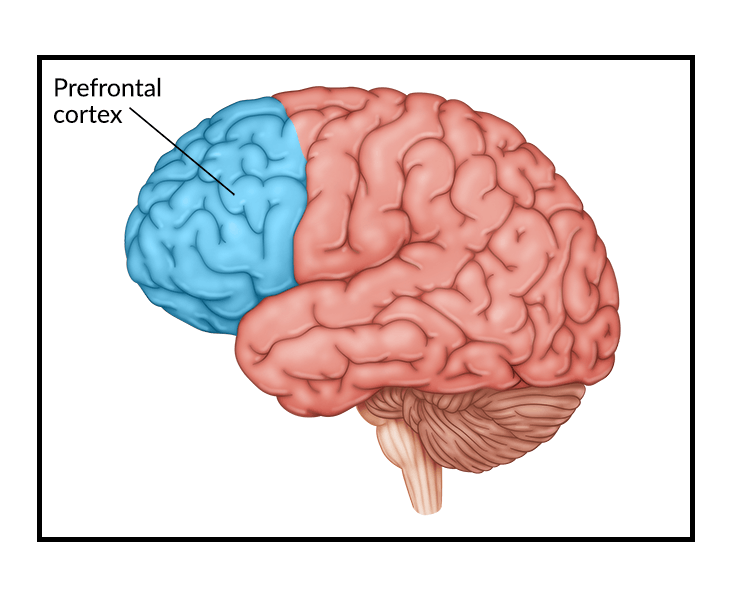

- Neuroscience of Intelligence: Research using fMRI has linked intelligence to prefrontal cortex activity, emphasizing the biological basis of cognitive abilities (Jung & Haier, 2007).

- AI and Adaptive Testing: Modern AI-driven tools like Pearson’s Q-interactive enhance testing accuracy by adapting to the test-taker’s ability level.

6. Conclusion

Intelligence tests remain a critical tool in psychology, education, and organizational settings. While they have evolved significantly since Galton and Binet, challenges like cultural bias and overemphasis on IQ persist. By understanding the nuances, incorporating ethical practices, and leveraging modern advancements, professionals can use these tools to foster growth and success across diverse domains.

7. References

- Deary, I. J., Strand, S., Smith, P., & Fernandes, C. (2007). Intelligence and educational achievement. Intelligence, 35(1), 13-21.

- Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Basic Books.

- Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. Bantam Books.

- Jung, R. E., & Haier, R. J. (2007). The Parieto-Frontal Integration Theory (P-FIT) of intelligence: Converging neuroimaging evidence. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 30(2), 135-154.

- Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. R. (2004). Emotional intelligence: Theory, findings, and implications. Psychological Inquiry, 15(3), 197-215.