Introduction

Imagine stepping into the early 20th century, where the human mind was still an enigma. At this juncture, psychoanalysis emerged as a groundbreaking school of thought, delving deep into the unconscious mind to understand human behavior. Pioneered by Sigmund Freud, this movement fundamentally changed the way we view emotions, thoughts, and the complexities of the psyche. Let us explore the origins, principles, methods, and legacy of psychoanalysis in this profound journey through the mind.

Historical Context

Psychoanalysis arose during a time when psychology was in its infancy, offering a revolutionary approach that challenged the rigid focus on observable phenomena. Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, introduced concepts that were as controversial as they were transformative.

Founding of Psychoanalysis

- Sigmund Freud (1856–1939): Freud was a neurologist whose clinical work with patients suffering from hysteria led him to explore the unconscious mind. His seminal work, The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), laid the foundation for psychoanalytic theory.

- Influence of Early Thinkers: Freud drew inspiration from philosophers such as Nietzsche and Schopenhauer, as well as from his mentor, Jean-Martin Charcot, who studied hysteria.

Key Principles of Psychoanalysis

Psychoanalysis introduced the notion that much of human behavior is driven by unconscious processes. It posited that unresolved conflicts, often rooted in childhood experiences, manifest in adult behavior.

Core Assumptions

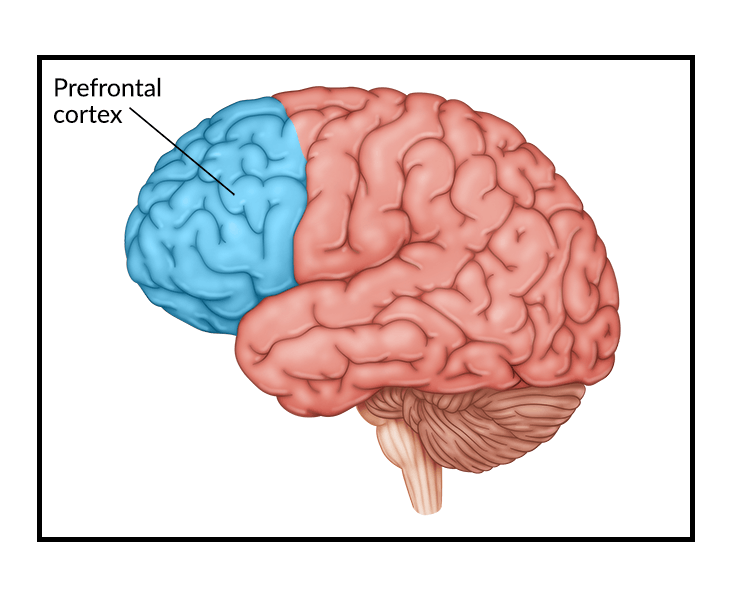

1. The Unconscious Mind

Sigmund Freud’s theory posits that the mind functions on three levels: conscious, preconscious, and unconscious. These levels interact and shape our thoughts, behaviors, and emotions.

- Conscious: This is the mental state that we’re aware of at any given moment—thoughts, perceptions, and ideas. For example, when you’re solving a math problem, you’re aware of each step you take.

- Preconscious: This contains thoughts and memories that are not currently in your awareness but can easily be brought to consciousness. An example is recalling your phone number or what you had for lunch yesterday.

- Unconscious: This is the largest and most influential part, containing thoughts, memories, desires, and feelings that are buried out of conscious awareness, often because they are too painful or socially unacceptable. Freud believed that the unconscious significantly impacts behavior, even though we are unaware of its influence. For instance, someone may have an unexplained fear of dogs due to a past traumatic experience they’ve forgotten but which still influences their reactions to dogs.

2. Psychosexual Development

Freud suggested that our personalities develop through a series of stages during childhood, each focused on a specific erogenous zone. These stages are key to understanding how early experiences shape adult behaviors and desires.

- Oral Stage (0-1 year): The infant’s primary source of pleasure is oral activities, such as sucking and biting. Fixations can occur here, leading to behaviors like smoking, overeating, or excessive talking in adulthood. For example, an adult who constantly chews gum might have unresolved oral-stage issues.

- Anal Stage (1-3 years): During this stage, the focus shifts to the control of bodily functions, particularly toilet training. The development of control and independence is important here. If parents are overly strict or too lenient during this stage, it can lead to either an overly tidy or excessively messy personality in adulthood. For instance, someone who is overly meticulous about organization may show signs of being “anal-retentive.”

- Phallic Stage (3-6 years): This stage is centered on the genitals. Freud believed that children experience the Oedipus complex (boys’ unconscious desire for their mother and rivalry with their father) or the Electra complex (girls’ desire for their father). Failure to resolve these conflicts can result in relationship issues in adulthood, such as anxiety in romantic situations.

- Latency Stage (6-puberty): During this period, sexual feelings are dormant, and children focus on developing social, intellectual, and communication skills. Friendships and learning take precedence.

- Genital Stage (puberty onward): The individual develops mature sexual relationships and a balanced personality. Successful navigation of earlier stages allows for healthy relationships and the ability to work productively in society.

3. Defense Mechanisms

Defense mechanisms are unconscious strategies the ego uses to protect itself from anxiety caused by conflicts between the id, ego, and superego. These mechanisms distort reality to prevent the person from experiencing stress or emotional pain. Freud’s daughter, Anna Freud, expanded on these mechanisms, which include:

- Repression: The unconscious blocking of distressing thoughts and memories. For example, a person who was abused in childhood might have no conscious memory of the event but could experience anxiety or depression in adulthood.

- Denial: Refusing to acknowledge a painful reality. A classic example is a person who continues to drink excessively despite being told by friends and family that they have a problem, denying the existence of their addiction.

- Projection: Attributing one’s own unacceptable thoughts or feelings to others. For instance, if someone feels angry but cannot acknowledge their anger, they might accuse others of being hostile or aggressive toward them.

- Displacement: Redirecting emotions from a “dangerous” object to a safer one. For example, a person who is angry at their boss might go home and take out their frustration by yelling at their partner or kicking the dog.

- Rationalization: Offering logical-sounding explanations for behaviors that are actually driven by internal conflicts or desires. For instance, someone who fails a test might rationalize it by saying, “The test was unfair,” rather than acknowledging that they didn’t study enough.

- Sublimation: Redirecting negative or socially unacceptable impulses into acceptable or productive activities. For example, someone with aggressive impulses might take up a sport like boxing or martial arts to channel their anger.

Goals of Psychoanalysis

- To uncover and resolve unconscious conflicts.

- To provide insight into the underlying causes of psychological distress.

- To foster personal growth and self-awareness.

Methodology

Free Association: The Gateway to the Unconscious

Patients were encouraged to speak freely about their thoughts, feelings, and memories without censorship. This technique aimed to reveal hidden patterns and unconscious conflicts.

Dream Analysis

Freud considered dreams the “royal road to the unconscious.” He analyzed their manifest (surface) and latent (hidden) content to uncover repressed desires and fears.

Case Studies

Freud’s work was largely based on detailed case studies, such as that of “Anna O.” and the “Rat Man,” which provided rich insights into the workings of the unconscious mind.

Table 1: Key Methods in Psychoanalysis

| Method | Description |

| Free Association | Exploring thoughts without judgment to access the unconscious |

| Dream Analysis | Interpreting dreams to uncover repressed conflicts |

| Case Studies | In-depth analysis of individual patients |

Criticisms of Psychoanalysis

Despite its revolutionary ideas, psychoanalysis faced significant criticism from both contemporary and modern psychologists.

Lack of Scientific Rigor

- Subjectivity: The theories relied heavily on subjective interpretations, making them difficult to test empirically.

- Small Sample Sizes: Freud’s reliance on case studies limited the generalizability of his findings.

Cultural Bias

- Freud’s theories were deeply rooted in the cultural norms of his time, often overlooking broader societal and cultural contexts.

Rival Schools

- Behaviorism: Championed by John B. Watson and B.F. Skinner, behaviorism rejected the focus on the unconscious, favoring observable behaviors.

- Humanistic Psychology: Figures like Carl Rogers criticized psychoanalysis for its deterministic view, emphasizing free will and self-actualization instead.

Legacy of Psychoanalysis

Despite its criticisms, psychoanalysis remains a cornerstone in the history of psychology. It paved the way for new therapies and enriched our understanding of the human mind.

Contributions to Psychology

- Therapeutic Techniques: Psychoanalysis gave rise to modern psychodynamic therapies, which are still widely practiced.

- Influence on Arts and Literature: Freud’s ideas permeated culture, inspiring works of art, literature, and film.

- Foundation for Other Theories: Psychoanalysis influenced subsequent schools of thought, including Jung’s analytical psychology and Adler’s individual psychology.

Conclusion

Psychoanalysis is a testament to the power of bold ideas. It dared to venture into the uncharted territories of the unconscious mind, offering profound insights into the human condition. While it may no longer dominate the field of psychology, its impact is indelible, shaping not only psychological theory but also our broader cultural understanding of the self.

References

- Freud, S. (1900). The Interpretation of Dreams. Macmillan.

- Breuer, J., & Freud, S. (1895). Studies on Hysteria. Franz Deuticke.

- Gay, P. (1988). Freud: A Life for Our Time. W.W. Norton & Company.

- Schultz, D. P., & Schultz, S. E. (2011). A History of Modern Psychology. Wadsworth Publishing.