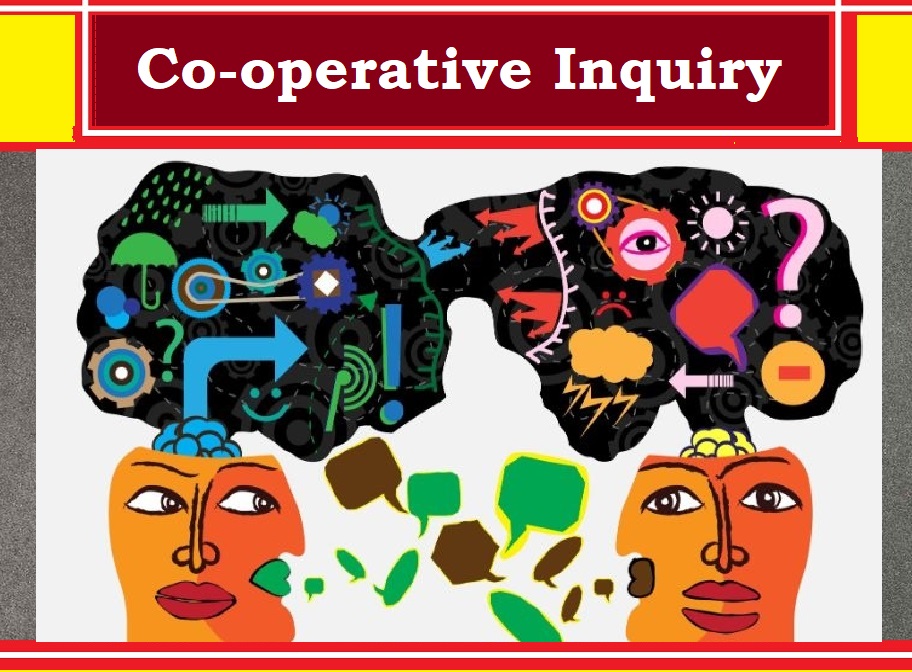

Paradigms of Western Psychology: Co-operative Inquiry

Co-operative inquiry is a participatory paradigm within Western psychology that emphasizes collaboration, shared experiences, and co-creation of knowledge. Developed by John Heron in the 1970s, it challenges the traditional hierarchical roles of researcher and participant by making all members equal co-researchers and co-subjects. This approach has gained traction in fields such as social psychology, community development, and organizational behavior.

Understanding Co-operative Inquiry

Co-operative inquiry is rooted in humanistic and participatory traditions. It operates on the premise that human beings are self-determining agents capable of reflecting on their experiences to create meaningful change. Unlike positivist paradigms that prioritize objective, detached observation, co-operative inquiry seeks to understand phenomena through collective reflection and action.

Core Principles of Co-operative Inquiry

- Participation: All members actively engage as both researchers and subjects, contributing equally to the inquiry process.

- Reflexivity: Ongoing reflection is a central component, ensuring that biases and assumptions are identified and addressed.

- Cyclic Process: Inquiry unfolds through iterative cycles of action and reflection.

- Experiential Knowing: Emphasis is placed on direct experience as a valid source of knowledge.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Co-operative Inquiry and Traditional Research

| Aspect | Traditional Research | Co-operative Inquiry |

|---|---|---|

| Researcher Role | Detached observer | Collaborative participant |

| Knowledge Generation | Objective, hypothesis-driven | Subjective, co-created |

| Methodology | Predominantly quantitative | Qualitative and participatory |

| Outcome Focus | Generalizable results | Context-specific insights |

The Process of Co-operative Inquiry

Co-operative inquiry follows a structured yet flexible process that ensures inclusivity and depth. Heron and Reason (1997) outlined four phases that form the cyclical foundation of this paradigm:

1. Initial Reflection

Participants collaboratively define the research question, establish shared goals, and explore assumptions. For example, a team of teachers and students might inquire into how classroom dynamics impact learning.

2. Action

Participants engage in actions or practices related to the inquiry. In the classroom example, teachers might implement new teaching strategies while students reflect on their experiences.

3. Reflection

Participants reconvene to discuss their experiences, analyze patterns, and identify areas for further exploration. Reflexive dialogue is key to uncovering hidden assumptions and generating deeper insights.

4. Revised Action

Insights from the reflection phase inform subsequent cycles of action and reflection, fostering iterative learning and adaptation.

Figure 1: The Co-operative Inquiry Cycle

Initial Reflection → Action → Reflection → Revised Action (repeat)

Applications of Co-operative Inquiry

Co-operative inquiry has been applied across diverse contexts, ranging from psychotherapy to organizational development. Below are notable examples:

1. Mental Health and Psychotherapy

Co-operative inquiry has been used to explore therapeutic practices, focusing on the lived experiences of both therapists and clients.

- Example: A group of therapists and clients collaboratively examined how mindfulness techniques influence emotional regulation. Through iterative cycles, they identified strategies that were most effective for specific challenges.

- Research Insight: Heron (1996) demonstrated that co-operative inquiry fosters a deeper understanding of therapeutic processes, empowering participants to shape interventions that resonate with their unique experiences.

2. Organizational Change

Organizations have adopted co-operative inquiry to address issues such as team dynamics, leadership development, and employee engagement.

- Example: Employees and managers at a manufacturing firm collaboratively explored ways to improve workplace communication, leading to actionable changes in meeting structures and feedback mechanisms.

- Research Insight: Reason and Bradbury (2001) found that co-operative inquiry enhances organizational adaptability by fostering a culture of shared learning and innovation.

3. Education and Learning

In educational settings, co-operative inquiry has been used to design curricula, enhance teaching methods, and promote student engagement.

- Example: A university conducted a co-operative inquiry with faculty and students to reimagine assessment practices, resulting in more inclusive and meaningful evaluations.

- Research Insight: Kember (2000) reported that participatory approaches like co-operative inquiry improve both learning outcomes and relational dynamics in educational environments.

Table 2: Examples of Co-operative Inquiry Applications

| Field | Focus | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Mental Health | Exploring mindfulness practices | Enhanced emotional regulation strategies |

| Organizational Behavior | Improving workplace communication | Actionable team dynamics improvements |

| Education | Rethinking assessment methods | Inclusive and effective evaluations |

Strengths of Co-operative Inquiry

1. Democratization of Research

Co-operative inquiry empowers participants by recognizing them as co-creators of knowledge rather than passive subjects.

- Example: In a community health project, residents collaborated with researchers to design interventions that addressed local needs.

2. Practical Relevance

Insights generated through co-operative inquiry are often directly applicable to the context in which the research takes place.

- Example: Teachers involved in a co-operative inquiry on classroom management implemented strategies that led to observable improvements in student engagement.

3. Holistic Understanding

By integrating multiple perspectives and types of knowing (e.g., experiential, propositional), co-operative inquiry provides a nuanced understanding of complex issues.

Critiques and Challenges of Co-operative Inquiry

1. Time-Intensiveness

The iterative, participatory nature of co-operative inquiry requires significant time and commitment from participants.

- Example: A co-operative inquiry into healthcare practices required multiple cycles over two years to achieve meaningful results.

2. Power Dynamics

Despite its emphasis on equality, co-operative inquiry is not immune to power imbalances that can influence group dynamics and decision-making.

- Example: In a co-operative inquiry involving community leaders and marginalized groups, dominant voices occasionally overshadowed others.

3. Subjectivity and Validity

The reliance on subjective experiences raises questions about the validity and generalizability of findings.

- Counterargument: Advocates argue that the depth and contextual relevance of insights compensate for the lack of generalizability.

Table 3: Strengths and Challenges of Co-operative Inquiry

| Aspect | Strength | Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Participation | Empowers individuals | Risk of power imbalances |

| Practicality | Directly applicable insights | Requires significant time and resources |

| Knowledge Generation | Holistic and context-specific | Limited generalizability |

Future Directions

Co-operative inquiry continues to evolve, with emerging areas of application and methodological refinement. Future research could focus on:

- Digital Co-operative Inquiry: Exploring how virtual platforms can facilitate participatory research across geographical boundaries.

- Cross-Cultural Applications: Adapting co-operative inquiry to diverse cultural contexts to address global challenges.

- Integration with Other Paradigms: Combining co-operative inquiry with methodologies like grounded theory or action research to enhance its scope and rigor.

Conclusion

Co-operative inquiry represents a transformative paradigm in Western psychology, emphasizing collaboration, reflexivity, and practical relevance. By challenging traditional researcher-participant dynamics, it fosters a more inclusive and holistic approach to understanding human experiences. While it faces challenges related to time, power dynamics, and subjectivity, its strengths in democratizing research and generating context-specific insights make it a valuable tool for addressing complex psychological and social issues. As it continues to evolve, co-operative inquiry holds promise for shaping more equitable and impactful research practices.

References

- Heron, J. (1996). Co-operative Inquiry: Research into the Human Condition. Sage.

- Heron, J., & Reason, P. (1997). The practice of co-operative inquiry: Research “with” rather than “on” people. Handbook of Action Research, 144-154.

- Kember, D. (2000). Action learning and action research: Improving the quality of teaching and learning. Psychology Press.

- Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (2001). Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice. Sage.