Psychology has evolved through various schools of thought, each bringing unique perspectives to understanding human behavior and mental processes. One of the most influential schools is Behaviorism, which emphasizes observable behavior over internal mental states. With its roots in the early 20th century, Behaviorism remains a cornerstone of psychology, providing valuable insights into learning, conditioning, and behavior modification.

What is Behaviorism?

Behaviorism focuses on the study of observable and measurable behaviors, rejecting introspective methods that explore thoughts, feelings, or unconscious motives. Behaviorists argue that behavior is shaped by environmental stimuli and learned through interactions with the environment. This school of thought underscores the importance of reinforcement and punishment in shaping behavior.

The famous Behaviorist mantra is, “Behavior is a product of the environment.” For instance, a child learning to say “please” when asking for something often results from positive reinforcement, such as receiving praise or a desired object.

Origins of Behaviorism

Behaviorism emerged as a reaction against the introspective methods of structuralism and psychoanalysis. The movement was pioneered by John B. Watson in the early 1900s, who argued that psychology should focus solely on observable behavior to achieve scientific objectivity (Watson, 1913).

Later, B.F. Skinner expanded the field by introducing the concept of operant conditioning, emphasizing reinforcement and punishment as key factors in behavior modification (Skinner, 1938). Other notable contributors include Ivan Pavlov, known for classical conditioning, and Edward Thorndike, who developed the Law of Effect.

Research findings highlight Behaviorism’s empirical foundation. For instance, Thorndike’s experiments with cats demonstrated the “Law of Effect,” where actions leading to favorable outcomes were more likely to recur (Thorndike, 1905). Similarly, Skinner’s work with pigeons and rats provided robust evidence for operant conditioning’s principles (Skinner, 1948).

Table: Contribution of Key Behaviorists

| Behaviorist | Contribution | Experiment/Concept |

|---|---|---|

| John B. Watson | Established Behaviorism | “Little Albert” experiment |

| Ivan Pavlov | Classical Conditioning | Dog salivation experiment |

| B.F. Skinner | Operant Conditioning | Skinner box experiments |

| Edward Thorndike | Law of Effect | Cats solving puzzles in a puzzle box |

Key Principles of Behaviorism

Behaviorism is built on several foundational principles:

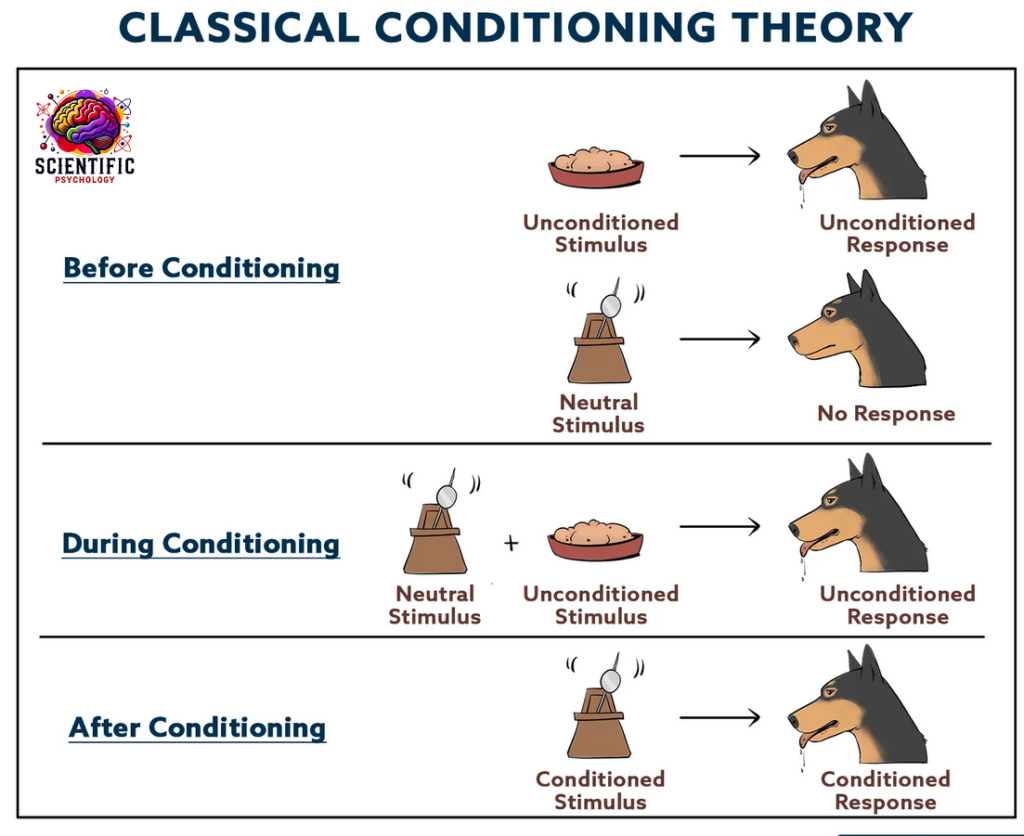

1. Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning involves learning through association, where a neutral stimulus becomes associated with a meaningful stimulus to elicit a conditioned response.

Example: Pavlov’s experiments with dogs demonstrated that pairing a bell (neutral stimulus) with food (unconditioned stimulus) led the dogs to salivate (conditioned response) upon hearing the bell.

Image: Pavlov’s Experiment

2. Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning focuses on how consequences shape behavior. Behaviors followed by positive outcomes are reinforced, while those followed by negative outcomes are discouraged.

Example: A teacher rewarding students with extra playtime for completing homework encourages the desired behavior.

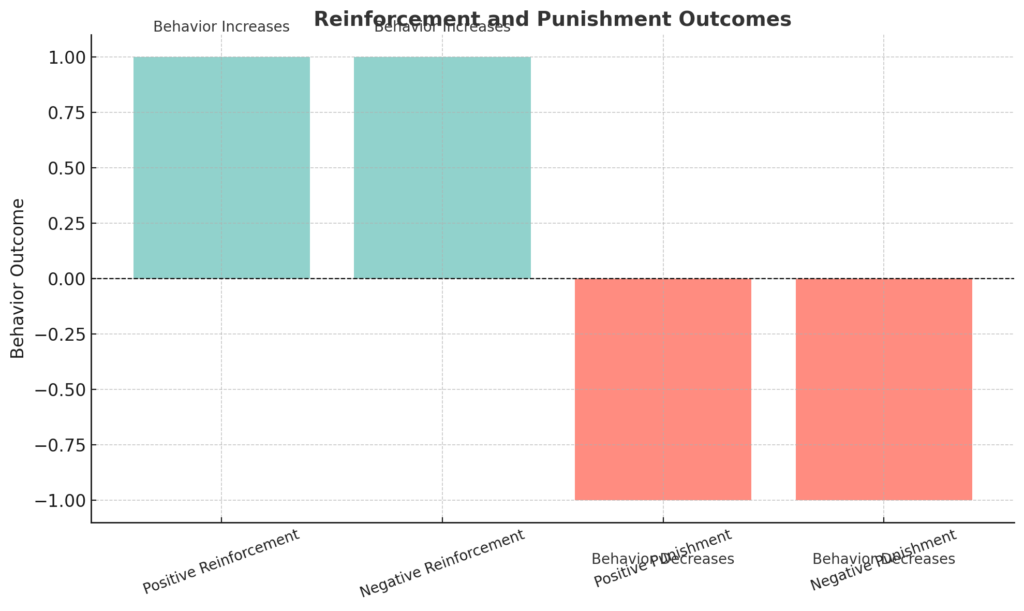

3. Reinforcement

Reinforcement increases the likelihood of a behavior being repeated.

- Positive Reinforcement: Adding a desirable stimulus (e.g., giving a treat for good behavior).

- Negative Reinforcement: Removing an unpleasant stimulus (e.g., turning off an annoying alarm when a task is completed).

4. Punishment

Punishment decreases the likelihood of a behavior being repeated.

- Positive Punishment: Adding an unpleasant stimulus (e.g., extra chores for misbehavior).

- Negative Punishment: Removing a desirable stimulus (e.g., taking away a toy for fighting).

5. Stimulus Generalization and Discrimination

- Generalization: Responding similarly to stimuli that are similar to the conditioned stimulus.

- Discrimination: Learning to respond only to a specific stimulus and not to similar ones.

Table: Classical vs. Operant Conditioning

| Feature | Classical Conditioning | Operant Conditioning |

| Focus | Association between stimuli | Consequences of behavior |

| Key Figures | Ivan Pavlov | B.F. Skinner |

| Example | Salivating at the sound of a bell | Pressing a lever for food |

Applications of Behaviorism

Behaviorism has practical applications in various domains, from education to therapy. Let us explore some real-world uses:

1. Education

Behaviorist principles guide classroom management and instructional strategies. Teachers use reinforcement and punishment to shape student behavior and learning.

Example: Using praise, stickers, or points as rewards for good performance motivates students to repeat desired behaviors.

A study by Alberto and Troutman (2006) demonstrated that positive reinforcement techniques significantly improved classroom behavior and academic performance in elementary school students.

2. Behavior Therapy

Behavior therapy addresses maladaptive behaviors by applying conditioning principles.

Example: Systematic desensitization, based on classical conditioning, helps individuals overcome phobias by gradually exposing them to feared stimuli.

A meta-analysis by Wolpe (1958) found systematic desensitization to be highly effective in treating anxiety disorders, particularly phobias.

3. Organizational Behavior

In workplaces, behaviorist strategies are used to improve employee performance through incentives and feedback.

| Principle | Example in the Workplace |

|---|---|

| Positive Reinforcement | Bonuses for meeting targets |

| Negative Reinforcement | Removing unnecessary tasks for efficiency |

| Punishment | Deductions for tardiness |

4. Parenting

Parents often use operant conditioning to shape their children’s behavior.

Example: Time-outs (negative punishment) discourage tantrums, while praise (positive reinforcement) encourages polite behavior.

Chart: Reinforcement and Punishment Outcomes

Examples to Illustrate Behaviorism

Example 1: Dog Training

Dog trainers use operant conditioning by rewarding dogs with treats for obeying commands (positive reinforcement) and ignoring undesired behaviors (negative punishment).

Example 2: Habit Formation

A person trying to develop a workout habit may reward themselves with a favorite snack after exercising (positive reinforcement), making the behavior more likely to recur.

Example 3: Smoking Cessation Programs

Behaviorist strategies such as contingency management offer tangible rewards (e.g., vouchers or cash) to individuals who successfully abstain from smoking, leveraging positive reinforcement to encourage quitting (Higgins et al., 2008).

Behaviorism’s Enduring Legacy

Behaviorism’s impact continues to resonate in contemporary psychology, particularly in areas like applied behavior analysis (ABA), which is widely used for individuals with autism and developmental disorders. This application highlights Behaviorism’s adaptability and relevance even in modern therapeutic settings.

Research Supporting ABA

Lovaas (1987) conducted a seminal study demonstrating that intensive ABA interventions significantly improved communication and social skills in children with autism. More recent meta-analyses, such as by Makrygianni et al. (2018), confirm ABA’s effectiveness in developmental interventions.

Expanding the Evidence Base

Study on Classroom Behavior

A study by Emmer and Evertson (2016) found that applying reinforcement principles in classrooms led to a 30% improvement in student engagement and a significant reduction in disruptive behaviors.

Application in Technology

Behaviorist principles have shaped user experience (UX) design. For instance, apps like Duolingo use positive reinforcement (streaks, badges) to encourage consistent learning behaviors (Landers et al., 2015).

Cultural Variations in Reinforcement

Research by Markus and Kitayama (1991) revealed cultural differences in how reinforcement is perceived. In collectivist cultures, social approval often serves as a stronger reinforcer than tangible rewards.

Research on Hybrid Approaches

Studies like those by Baer et al. (1968) advocate combining Behaviorist and Cognitive frameworks to create more comprehensive behavioral models, particularly in educational and clinical settings.

Criticisms and Limitations of Behaviorism

While Behaviorism has been instrumental in advancing psychology, it is not without criticism:

- Neglect of Internal Processes: Critics argue that Behaviorism overlooks mental processes such as thoughts, emotions, and motivations, which are crucial for understanding human behavior (Chomsky, 1959).

- Overemphasis on the Environment: Behaviorism places excessive focus on environmental factors, underestimating the role of genetics and innate traits.

- Limited Scope: The theory is less effective in explaining complex behaviors like creativity or problem-solving, which involve higher cognitive functions.

Modern Critiques and Future Directions

Behaviorism’s focus on observable behavior has been both a strength and a limitation. Modern critiques suggest integrating cognitive perspectives to address complex phenomena like decision-making and emotion regulation (Bandura, 1977).

Conclusion

Behaviorism has left an indelible mark on psychology, providing a scientific framework for studying behavior. Its principles have practical applications in education, therapy, workplaces, and beyond. Despite its limitations, Behaviorism’s emphasis on observable and measurable behaviors ensures its continued relevance in understanding and influencing human actions.

As we navigate a world filled with stimuli and responses, Behaviorism reminds us of the powerful role our environment plays in shaping who we are. By understanding and applying its principles, we can create environments that foster positive behaviors and personal growth.

References

- Alberto, P. A., & Troutman, A. C. (2006). Applied Behavior Analysis for Teachers. Pearson Education.

- Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., & Risley, T. R. (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1(1), 91–97.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. Prentice Hall.

- Chomsky, N. (1959). A Review of B.F. Skinner’s Verbal Behavior. Language.

- Emmer, E. T., & Evertson, C. M. (2016). Classroom Management for Middle and High School Teachers. Pearson.

- Higgins, S. T., et al. (2008). Contingency Management Interventions for Smoking Cessation. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment.

- Landers, R. N., Bauer, K. N., & Callan, R. C. (2015). Gamification of task performance with leaderboards: A goal-setting experiment. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 508–515.

- Lovaas, O. I. (1987). Behavioral treatment and normal educational and intellectual functioning in young autistic children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55(1), 3–9.

- Makrygianni, M. K., Gena, A., Katoudi, S., & Galanis, P. (2018). The effectiveness of applied behavior analytic interventions for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A meta-analytic study. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 51, 18-31.

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253.

- Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned Reflexes. Oxford University Press.

- Skinner, B. F. (1938). The Behavior of Organisms. Appleton-Century.

- Thorndike, E. L. (1905). The Law of Effect. Psychological Monographs.

- Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It. Psychological Review.

- Wolpe, J. (1958). Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition. Stanford University Press.