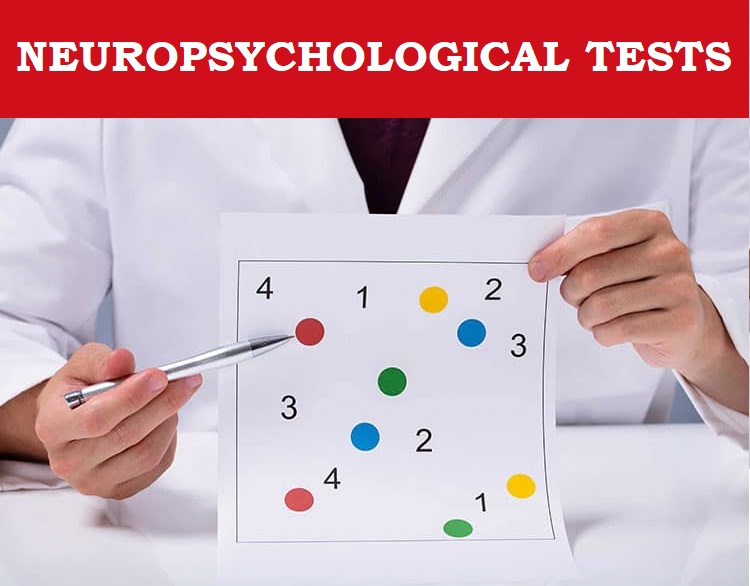

#Psychological #Testing #Neuropsychological #Tests

Neuropsychological testing is a cornerstone in understanding the relationship between brain function and behavior. By employing standardized tools, neuropsychological tests help clinicians assess cognitive, motor, emotional, and behavioral functioning.

1. Historical Development of Neuropsychological Testing

The evolution of neuropsychological tests reflects advancements in neuroscience, psychology, and clinical applications. Below is a timeline of significant milestones:

Early Foundations

- 19th Century: Neuropsychological assessment began with localization theories by Paul Broca and Carl Wernicke, who identified specific brain areas associated with language.

- 1905: Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon developed the Binet-Simon Intelligence Scale, the precursor to cognitive testing.

Mid-20th Century

- Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Battery (HRNB) (1947): Developed by Ward Halstead and Ralph Reitan, the HRNB was the first standardized battery to assess brain damage.

- Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) (1955): Created by David Wechsler, this test became essential in neuropsychological evaluations, measuring verbal and performance IQ.

Modern Developments

- Luria-Nebraska Neuropsychological Battery (LNNB) (1973): Inspired by Alexander Luria’s work, this battery emphasized qualitative analysis and flexibility in assessing brain injury.

- Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (1975): Designed by Folstein et al., MMSE became a quick tool for assessing cognitive impairment.

- Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) (1986): An automated, computerized battery assessing attention, memory, and executive functions.

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (2005): Developed by Nasreddine et al., MoCA gained prominence for early detection of mild cognitive impairment.

Timeline of Key Neuropsychological Tests

| Test/Model | Author(s) |

| Broca’s Area Localization | Paul Broca |

| Binet-Simon Intelligence Scale | Alfred Binet, Theodore Simon |

| Halstead-Reitan Battery | Ward Halstead, Ralph Reitan |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale | David Wechsler |

| Luria-Nebraska Battery | Charles Golden |

| Mini-Mental State Examination | Folstein et al. |

| Cambridge Neuropsychological Battery | CANTAB Authors |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment | Ziad Nasreddine |

2. Types of Neuropsychological Tests and Their Applications

Neuropsychological tests can be categorized based on the domains they assess. Each category has distinct applications and strengths:

2.1. Intelligence and General Cognitive Function

- Examples: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales.

- Applications: Useful in diagnosing intellectual disabilities, assessing brain injury severity, and evaluating cognitive decline in dementia.

- Practical Example: Comparing pre- and post-injury IQ scores to evaluate cognitive recovery.

2.2. Memory

- Examples: Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS), California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT).

- Applications: Diagnosing amnestic syndromes, evaluating memory in Alzheimer’s disease.

- Practical Example: Using CVLT to assess recall and recognition performance.

2.3. Executive Function

- Examples: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), Stroop Test.

- Applications: Evaluating problem-solving, flexibility, and inhibitory control in conditions like ADHD or frontal lobe injury.

- Practical Example: Administering the WCST to assess cognitive flexibility in a patient with traumatic brain injury.

2.4. Language

- Examples: Boston Naming Test (BNT), Token Test.

- Applications: Diagnosing aphasia, assessing language recovery post-stroke.

- Practical Example: Using BNT to track language deficits in stroke rehabilitation.

2.5. Attention and Processing Speed

- Examples: Trail Making Test (TMT), Continuous Performance Test (CPT).

- Applications: Diagnosing ADHD, assessing processing speed in multiple sclerosis.

- Practical Example: Measuring task-switching ability with TMT.

| Test Type | Examples | Applications |

| Intelligence | WAIS, Stanford-Binet | IQ assessment, cognitive decline diagnosis |

| Memory | WMS, CVLT | Alzheimer’s, traumatic amnesia |

| Executive Function | WCST, Stroop Test | ADHD, frontal lobe disorders |

| Language | BNT, Token Test | Aphasia, stroke recovery |

| Attention | TMT, CPT | ADHD, processing speed |

3. Critical Evaluation of Neuropsychological Tests

3.1. Strengths

- Comprehensive Analysis: Provides detailed insights into specific cognitive domains.

- Diagnostic Accuracy: Crucial for identifying neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or brain injuries.

- Research Applications: Forms the basis for understanding brain-behavior relationships.

3.2. Weaknesses

- Cultural and Educational Bias: Tests like the WAIS may disadvantage individuals from non-Western backgrounds.

- Time-Consuming: Batteries like HRNB require hours to administer.

- Subjectivity: Qualitative approaches, such as LNNB, can introduce examiner bias.

4. Practical Advice for Learners and Practitioners

4.1. Test Selection

- Tip: Match the test to the patient’s condition. For example, use MoCA for early-stage dementia and WCST for executive dysfunction.

4.2. Administration Tips

- Standardization: Follow strict protocols to ensure reliability.

- Cultural Adaptation: Use culturally adapted versions (e.g., Hindi MoCA).

- Environment: Administer tests in a quiet, distraction-free setting.

4.3. Interpreting Results

- Contextual Understanding: Consider patient history and current functioning.

- Actionable Example: A patient scoring below the cutoff on MMSE may require further imaging to confirm dementia.

| Practical Steps for Practitioners |

| Choose tests aligned with diagnostic goals. |

| Adapt tests for cultural and linguistic relevance. |

| Integrate results with patient history and clinical observations. |

5. Relevant Research and Advances

- Cognitive Reserve: Stern (2009) highlighted that higher education and cognitive engagement mitigate neurodegeneration effects.

- Digital Assessments: Recent studies explore mobile applications for neuropsychological testing (e.g., iPad-based MoCA).

- Neuroimaging Correlation: fMRI studies link neuropsychological scores to brain activity, enhancing diagnostic precision (Smith et al., 2013).

6. Conclusion

Neuropsychological tests have transformed our understanding of the brain and its functions. While they offer immense diagnostic and research value, addressing cultural biases and ensuring rigorous administration are critical. For learners and practitioners, mastering these tools means not only understanding their technicalities but also applying them thoughtfully to improve lives.

References

- Stern, Y. (2009). Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia, 47(10), 2015-2028.

- Smith, S. M., Fox, P. T., Miller, K. L., et al. (2013). Functional connectomics from resting-state fMRI. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17(12), 666-682.

- Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). Mini-mental state. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189-198.

- Nasreddine, Z. S., Phillips, N. A., Bédirian, V., et al. (2005). The Montreal Cognitive Assessment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(4), 695-699.